From Hardwood to Healing: The Chris Herren Story

Chris Herren's rise, fall, and recovery from addiction is a powerful reminder that no one is beyond saving. From NBA hopeful to overdose survivor, he now uses his story to inspire hope and help others choose a different path.

“I remember when I was in high school, I was sitting in a chair just like you, listening to someone like me, thinking: ‘That will never be me.’”

Chris Herren has opened countless talks in school gymnasiums and auditoriums with those words. Over the past decade, he has spoken to more than two million students across the country, averaging over 200 speaking engagements per year. His mission: to confront the realities of drug and alcohol addiction with honesty, vulnerability, and hope.

In numerous interviews, Herren has pushed to shift the narrative around addiction—away from the sensationalism of “rock bottom” stories (a term he openly despises) and toward a deeper focus on the first time someone uses, and the reasons why.

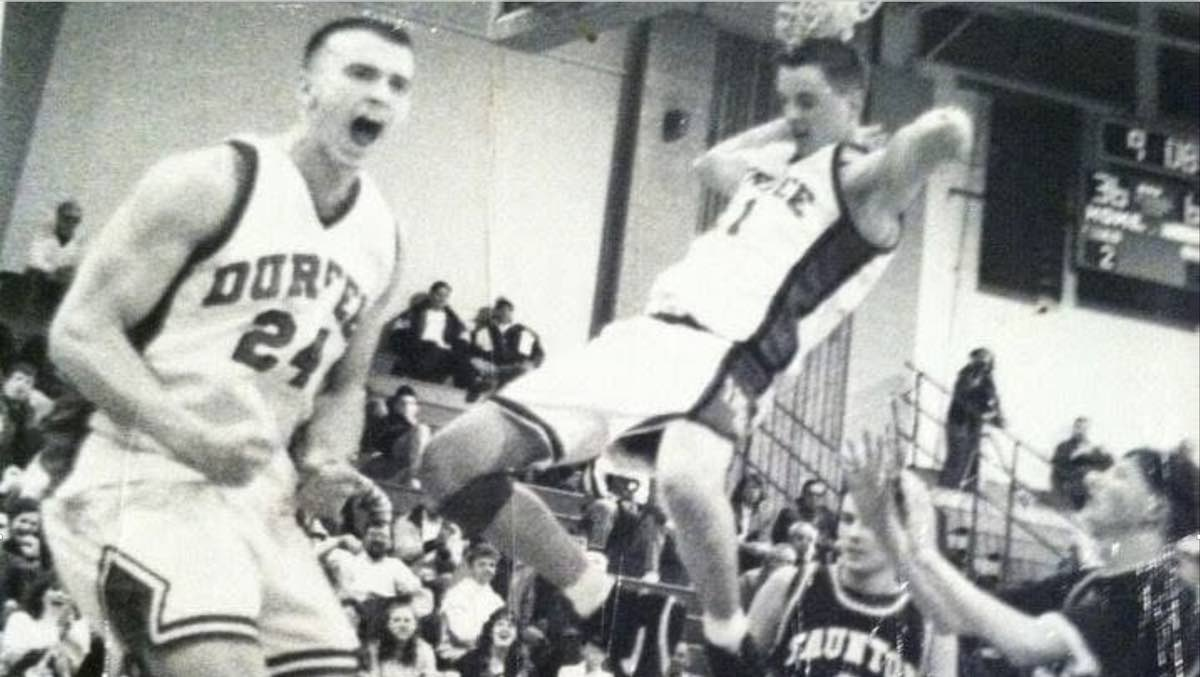

In the early 1990s, Chris was one of the most highly recruited high school basketball players in the country. But before he ever stepped onto the court at B.M.C. Durfee High School in Fall River, his older brother, Mike, had already cast a long shadow.

Mike established himself as a Fall River legend by leading Durfee to back-to-back Massachusetts state championships in 1988 and 1989. What he lacked in raw athleticism, he made up for with toughness and leadership.

This was the pressure Chris walked into at Durfee. By then, Chris was already sneaking drinks from his father’s liquor cabinet. His father—a prominent politician in the blue-collar city of Fall River—struggled with alcoholism, and his parents’ marriage was beginning to fracture.

Looking back, Chris summed it up simply: “Here I was, a fourteen-year-old, playing in front of 4,000 or 5,000 people.”

Chris never did win a state title at Durfee. He left as the school’s all-time leading scorer with 2,073 points and earned a coveted spot in the 1994 McDonald’s All-American Game—one of the most prestigious honors in high school basketball.

Bill Reynolds was a beloved, longtime sports columnist for The Providence Journal, known not just for his storytelling, but for the heart he brought to it. For Chris Herren, Reynolds was more than a reporter—he was the first adult who didn’t treat him like an exhibit at a zoo. He didn’t come around to gawk or sensationalize. He came to understand.

In 1993, recognizing that Chris was something special, Reynolds decided to follow the Durfee High School basketball team for an entire season. The result was Fall River Dreams, a book that captured not only the rise of a young basketball star, but the complicated fabric of a working-class city that pinned its hopes on him.

It was the beginning of a rare and beautiful relationship between sportswriter and subject—one built on trust, honesty, and mutual respect. Years later, that bond led to a second book: Basketball Junkie: A Memoir, co-written by Reynolds and Herren, chronicling the athlete’s harrowing descent into addiction and his long road to recovery.

Reynolds passed away in July 2023, but his legacy lives on—not just in the words he wrote, but in the lives he touched, including Chris Herren’s.

Herren had his pick of elite college basketball programs—Syracuse, Kentucky, Duke. But in the end, he chose to stay close to home, committing to Boston College, just a short drive up Route 24 from Fall River. It felt like the safe choice, but it proved to be a mistake.

Within weeks of arriving on campus, Chris walked into a dorm room and was offered cocaine for the first time. Thoughts of Len Bias were fresh in his mind—Bias had died of a cocaine overdose in 1986, just hours after being drafted by the Boston Celtics. It was reportedly his first and only time using the drug. Despite the warning signs and that haunting memory, Chris did his first line of cocaine anway.

In his first game for Boston College, Chris scored 14 points—early flashes of the brilliance everyone expected. But then came a hard fall and a broken wrist. His season was over before it ever truly began. Without basketball to ground him, he started to drift—partying on campus and making more frequent drives down Route 24 to hang out with his longtime friends in Fall River.

He failed multiple drug tests, and eventually, Boston College dismissed him from both the team and the university. For the first time, Herren’s addiction came with real consequences.

Just a year earlier, he was one of the most sought-after recruits in the country. Now, he was a pariah—radioactive. No one wanted to go near him.

No one except Jerry Tarkanian.

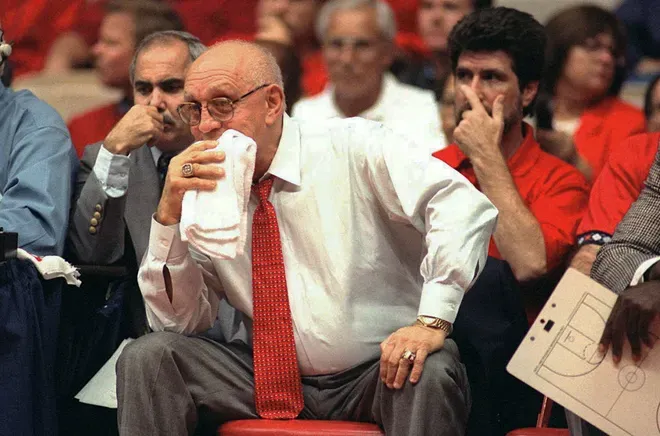

Maybe Tarkanian saw something familiar in Herren. A misfit. A fighter. A kid the system had given up on. Tarkanian had built a career out of second chances. He was fiercely loyal and defiantly unconventional, a coach who welcomed transfers, prospects who hadn't panned out, and players with baggage. Where others saw risk, Tark saw reward.

He had found national success at UNLV in the 1980s, leading the Runnin’ Rebels to a national championship and becoming famous for nervously chewing on a white towel during games. But his unconventional methods—and the type of players he embraced—came at a cost. Critics accused his program of turning a blind eye to gambling connections, drug use, and improper benefits. Whether fair or not, Tarkanian carried a reputation for running a program that blurred the lines.

When photos surfaced of UNLV players in a hot tub with known gamblers and boosters, Jerry Tarkanian found himself on the hot seat—again. The NCAA was circling, and public pressure mounted. Rather than expose his players to more scandal or see the program dragged further, Tarkanian resigned. Some said he stepped down to protect the team. Others said he left before he could be pushed out.

He took a shot at the NBA, coaching the San Antonio Spurs, but it didn’t last long. Tarkanian’s style never quite fit the professional game. He belonged in college basketball. Before long, he returned to it, this time at Fresno State, a smaller program hungry for relevance and redemption.

For Chris Herren—fresh off a drug suspension and a public fall from grace—Fresno State wasn’t just a second chance. It was a lifeline. And in Jerry Tarkanian, he found the perfect coach. Tarkanian didn’t just see a kid with problems. He saw a competitor. A fighter. Someone the world had written off. But like Bill Reynolds before him, Tarkanian saw something worth saving in the kid from Fall River.

Chris Herren still remembers the first time he met Jerry Tarkanian. “Tarkanian looked at me and said, ‘I’m a fan of second chances,’” Herren recalls. “I’ll never forget that line.”

In December 1996, Herren returned to Massachusetts to play against UMass in Springfield, just a couple hours from his hometown of Fall River. The crowd hadn’t forgotten how things ended for him at Boston College, and they didn't give him a warm welcome. In fact, they were pretty hostile towards him.

Herren fed off the emotion of the crowd and put on a show. He poured in a career-high 25 points and led Fresno State to a hard-fought, emotional win. By the final buzzer, some in the crowd had started to come around. It was a glimpse of what could have been.

At Fresno State, Herren played some of the best basketball of his life. Under Tarkanian’s guidance, he became a fearless floor general, averaging nearly 18 points and 8 assists, resurrecting the Bulldogs’ national profile and leading them to the NCAA Tournament. On the court, it looked like Herren's career trajectory was back on track.

But beyond the view of the cameras and fans, his addiction deepened. By his own admission, Herren failed multiple drug tests during his time at Fresno—and the program often looked the other way. Winning still came first. As long as he produced, his problems remained in the background, quietly escalating.

In the 1997–98 season, after one of his failed drug tests became public, Chris Herren left the team to enter rehab, spending 21 days in a treatment center. It was the first time while at Fresno State that the public saw that Herren was still fighting his demons.

When Herren admitted to his cocaine relapse in November 1997, he faced the cameras at a press conference to announce his suspension. Standing beside him was Jerry Tarkanian. While most coaches might have distanced themselves to protect the program, Tarkanian didn’t flinch. He stood by Herren without hesitation.

To the media, his message was clear: this wasn’t the end. It was a setback—not a surrender. Tarkanian believed in redemption, and he wasn’t giving up on the kid he’d taken a chance on.

Herren would return to the team and finish his college career at Fresno State. The Bulldogs, under his lead, reached national rankings and returned to the NCAA Tournament—heights the program hadn’t touched in years. But off the court, his addictions still lingered. And while Fresno State basked in basketball success, the university continued to look the other way. As long as he delivered wins, few asked what it was costing him to do so.

Chris Herren’s lifelong dream came true on June 30, 1999, when he was selected in the second round of the NBA Draft—33rd overall by the Denver Nuggets. But the night didn’t feel like a celebration.

Local media had gathered at his family’s home in Fall River, cameras ready to capture the joy of a first-round pick. But as the names kept getting called—and none of them were his—the mood shifted. The disappointment in the room was palpable. His brother was overheard venting each time a team passed on Chris. Chris himself tried to appear composed, but the frustration showed in his face and body language. The moment that should have been filled with joy felt more like a wake.

Still, he had made it. And by many accounts, Herren’s lone season in Denver was the cleanest he had been in years. The veterans on that Nuggets team knew about his troubled past and made it a point to look out for him. There was structure, accountability, and—for the first time in a long while—stability.

Herren was being held accountable—not just as a player, but as a man. Denver was good for him. It was thousands of miles from Fall River.

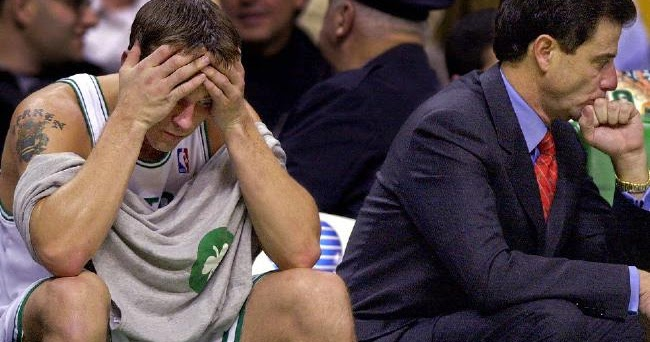

But after just one season, that distance vanished. In the summer of 2000, Herren was traded to his hometown team—the Boston Celtics. On paper, it looked like the ultimate dream: the local kid coming home to wear Celtics green and carry on the legacy of the players he grew up idolizing—Bird, McHale, and Parish.

But for Herren, it marked the beginning of another downward spiral.

Coming back to Boston meant coming back to Fall River—and everything that came with it. Old friends. Old habits. Old dealers. The structure and accountability he had in Denver disappeared, and in its place came familiarity, temptation, and pressure. What should have been a dream come true became a nightmare come to life.

The weight and pressure of returning as a hometown hero only deepened his fear of being exposed for what he had become. Behind the scenes, his addiction returned—this time, stronger than before.

One of the most haunting stories Chris Herren tells from his time with the Celtics lays bare just how deeply addiction had consumed him. Minutes before a game, dressed in full uniform, he walked out to the team parking lot—not to greet fans or stretch his legs, but to meet a drug dealer. He had arranged a delivery of OxyContin, and with the clock ticking toward tip-off, he took the pills right there in the lot before heading back into the arena. It wasn’t about getting high anymore—it was about being able to function.

The image of a professional athlete, moments from being introduced to a sold out arena as the starting point guard for one of the NBA’s most storied franchises, sneaking out to score drugs while wearing his uniform is hard to believe – but it happened.

The year he spent with the Celtics was nothing like the dream he had as a young boy growing up in Fall River. His lifestyle had finally caught up to him.

On the court, the fire he’d relied on for so long was gone. His athleticism, which had once carried him through high school and college, was no match for the likes of Shaquille O’Neal or Michael Jordan. What he needed now was his brother’s grit—Mike’s toughness, his guile. But Chris’s heart wasn’t in it anymore. Maybe it never truly had been.

After just one season, the Celtics released him. And just like that, the NBA dream was over.

What followed was even darker. Chris Herren’s life and basketball career spiraled further out of control. He bounced between international teams—China, Turkey, Italy, Poland, Iran—places where no one knew him and no one asked questions. Despite not speaking the native languages, Herren always managed to secure drugs.

He played games high, sometimes injecting heroin or crushing painkillers in locker rooms or hotel bathrooms before tip-off.

Chris Herren has admitted to spending up to $25,000 a month on drugs during his darkest stretches, much of it on OxyContin and heroin. He was using up to 1,600 milligrams of OxyContin daily—an amount that could kill most people.

What had started as a way to escape having to be Chris Herren quickly became a full-time obsession, draining bank accounts, and erasing any remnants of the life he once had.

Herren was no longer a basketball player—he was a drug addict. The game that had once held the promise of generational wealth had become a means to an end: a paycheck to fund his habit. Every dollar he earned went to feeding his addiction– either staying high or avoiding the sickness of withdrawal. In chasing the next fix, he nearly lost everything—his career, his family, and his life.

His personal life was unraveling. He was arrested multiple times, overdosed more than once, and in 2004, was even pronounced clinically dead for about 30 seconds. He had tried rehab more than a dozen times, often relapsing just days after release. The once-celebrated All-American and NBA hopeful was now sleeping in his car, stealing from his family, and flirting with death.

During one of his worst relapses, he was found lying in a back alley in Providence, Rhode Island—shoeless, barely conscious, and fading. He had overdosed again. The needle he had used to shoot up was still in his arm.

Herren has said it was around that time he came to the realization that he had become one of those people that pedestrians were afraid of—someone they crossed the street to avoid.

It was a far cry from his days as a kid in Fall River when he was treated like a god and people would stumble over each other to get near him.

Chris Herren tells another story – sadly there are many – about a morning when he had just dropped his kids off at the school bus. Instead of heading home, he went to the liquor store to buy some vodka and he called his dealer. Numb and spiraling, he got behind the wheel and crashed his car into the gates of a cemetery.

As paramedics were attending to him at the scene of the crash, he couldn't stop thinking he had to pick his kids up off the bus that afternoon.

Herren was taken to the hospital. He decided to leave the hospital before being discharged. As he was sneaking out, he was thinking about how he was going to end his life. He felt he had become a burden and an embarrassment on his family.

As he was walking through the parking lot, a nurse was chasing after him, calling out his name. When he turned around, she looked at him and said quietly, “I knew your mother.”

Her words landed harder than any slap across the face or ice-cold bucket of water poured over his head.

His mother had passed away a few years earlier, Her dying wish was to see Chris get sober. She didn't get to see it happen.

The nurse didn’t scold him. She didn’t lecture him. She just wanted him to know that he was loved. Not for being Chris, the basketball prodigy – but for being Chris, the human being. Chris, the son.

When the nurse brought Chris back to the hospital, another unexpected lifeline appeared—one that if the nurse hadn't intervened, he never would have received.

Liz Mullin, the wife of former NBA All-Star Chris Mullin, had heard about his struggles. Liz arranged for him to enter a long-term rehab facility in Rhode Island—one of the few willing to take him despite his long history of relapses.

It wasn’t just a favor. It was an act of grace. Liz Mullin didn’t owe him anything, but she saw the good that still lay somewhere within Herren.

That moment changed everything. With nothing left to lose, Chris Herren entered treatment one final time.

But it wasn't without one last hiccup.

Chris's wife, Heather, was pregnant with their third child when Chris checked in for rehab. When she went into labor, Chris begged to be allowed a twenty-four hour leave to be with Heather at the birth of their son, Drew.

He had made significant progress, earning enough trust to be granted a temporary pass to leave. It should have been one of the most joyful, meaningful days of his life—a chance to be present, to be sober while holding his newborn son.

He arrived at the hospital and held Drew in his arms for a long time, overwhelmed with emotion. Across the room, he looked at his wife—the girl he had loved since seventh grade, the woman who had carried the full weight of their vows: “in sickness and in health.” And for years, it had been mostly sickness.

After a while, Chris said he needed to go for a walk. He proceeded to call his dealer and got high. When he returned to the hospital, Heather knew right away. She offered him an ultimatum. Go back to rehab now and get clean, or stay away from her and their children forever.

The thought of Len Bias dying wasn’t enough to stop him from doing his first line of cocaine.

The fear of being caught by a security guard outside the FleetCenter—while in full uniform—didn’t stop him from making a drug deal in the parking lot before a game.

The risk of being arrested in a foreign country didn’t stop him from accepting a drug delivery from a friend while playing in Turkey.

Even the thought of his mother's dying wish to see him sober wasn't enough.

But the thought of losing Heather and their three kids? That rattled him.

On August 1, 2008, Chris Herren scored his biggest victory. That date became more than a sobriety milestone—it became the start of a true comeback. Not on the court, but in life.

What followed wasn’t just recovery. It was purpose. Herren began sharing his story—as painful and embarrassing as it must be to relive every single day for the last fifteen years.

What started as a few small talks grew into a national mission. He began speaking in school gyms, treatment centers, juvenile halls, prisons, and athletic programs across the country. He didn’t glamorize addiction. He didn't want anyone feeling bad for him.

I’ve heard Chris Herren speak in person. He doesn’t come off like a therapist or a psychiatrist—and that’s exactly why kids listen. He speaks with passion, honesty, and in plain English. He knows teenagers tune out lectures and clinical talk, so he talks to them on their level. He makes eye contact with seemingly every student in the room. And if someone is rolling their eyes or scrolling through their phone, he’ll call them out—not to embarrass them, but to make sure they know someone is paying attention to them.

He doesn’t lecture—he relates. He’s been there. He speaks from experience. He was the kid in the back of the room, throwing spitballs while a guest speaker was talking.

Whether he’s talking to high school students in a gymnasium or Division I athletes in a locker room, he often starts the same way: “I was sitting in a chair just like you, thinking I’d never be that guy.”

He knows the pressure to fit in. To be cool. To pretend you're someone you're not.

He understands how drugs can make you feel—or make you not feel. He gets the allure. But he's also lived the consequences.

Chris Herren has traveled that road so others don’t have to. And if someone is already speeding down that superhighway to disaster—like he once was—he knows the exits. He knows the way back.

Over time, his story began to resonate.

His vulnerability and brutal honesty became his strength—and his mission was simple: if one kid heard him and chose a different path, it was worth it.

His message reached a national audience when ESPN aired its 30 for 30 documentary Unguarded in 2011, directed by Jonathan Hock. The film offered an unflinching look at Herren’s rise, fall, and recovery—combining archival footage, interviews, and raw personal narration.

It wasn’t just a sports documentary. It was a brutally honest account of addiction: from high school phenom to NBA hopeful to heroin addict, overdose survivor, and finally—man in recovery. It captured not only what Herren lost, but also the cost to his wife, his children, and his community.

Unguarded didn’t just tell his story—it shined more light on his mission. Suddenly, his journey wasn’t confined to school gymnasiums or locker rooms. It was being talked about at water coolers, around dinner tables, and in coffee shops. His message had gone national.

In 2011, he founded The Herren Project, a nonprofit dedicated to helping individuals and families affected by addiction. What began as a small initiative quickly became a national movement grounded in support, prevention, and recovery. The organization offers treatment placement assistance, recovery coaching, family support groups, and school-based prevention programs—most of it free.

Herren knew how hard it was to ask for help. His mission was to make sure that when someone did, help was there.

Chris Herren wore the number 24 for most of his basketball career. Today, in one of the few subtle nods to that part of his life, he limits the number of "guests" (that is how he refers to them) at his recovery facilities to just twenty-four. Herren believes in keeping things small, personal, and focused. Every person matters. Every story counts.

One of the most impactful elements of the Herren Project is its work with youth—empowering kids to make healthy choices long before addiction starts. Programs like Project Purple encourage students to stand up against substance use and embrace self-worth over peer pressure.

For Herren, this has become his purpose in life. This has become his calling.

Chris Herren’s story teaches us that addiction doesn’t discriminate—and that recovery isn’t a one-time event. It’s a daily choice.

In a recent interview, Herren reflected on how sobriety isn’t a straight line. He said the first ten years came relatively easy—structured, purposeful, and filled with service. But when the COVID-19 pandemic hit and the world shut down, everything changed. Quarantines, isolation, and the sudden halt of in-person speaking engagements made the last few years the hardest he’s faced since getting sober in 2008. The boredom and loneliness brought back temptations he thought he had long since buried.

It was a sobering reminder that recovery is never finished—it’s a lifelong commitment that requires constant vigilance.

Chris's life journey shows that talent, success, or even a loving family can’t shield someone from addiction. He had everything—fame, a pro career, and people who cared. But addiction still found him, and once it did, it stripped away everything. Until all that was left was a choice: live or die.

But his story also offers something just as powerful: hope.

Recovery is possible—even after a dozen failed rehab attempts, public collapse, and near-death experiences. Herren reminds us that no one is too far gone, and that second chances don’t just come from treatment centers—they come from people who believe in you when you can’t believe in yourself. People like Bill Reynolds, Jerry Tarkanian, the nurse at the hospital, Liz Mullin, Heather.

Now is Chris Herren's time to pay it forward and he is doing just that.

Chris Herren doesn’t claim to be a hero. He’s just a man who nearly died—more than once—and now wakes up every day trying to help those that society has given up on.

(If you or someone you love is struggling with addiction, visit The Herren Project for free support and recovery resources, or call the SAMHSA National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) — free, confidential help available 24/7.)

📢 Share on:

- Facebook: Click to share

- Twitter/X: Click to tweet

- LinkedIn: Click to share

One of Herren's full presentations before a gymnasium full of students. Must watch if you ever have the time.